Quickstart#

This notebook demos the core features of pymer4 models, which are intentionally designed to be similar to their R counter-parts with numerous quality-of-life features and enhancements.

Installation#

First follow the installation guide to setup pymer4 using conda or Google Collab

Picking a model#

pymer4 provides 4 types of models that share a consistent API:

Loading data#

All models work with polars Dataframes. If you are coming from pandas you can easily convert between libraries, but you should also seriously consider switching:

pandas->polars:import polars as pl; pl.DataFrame(pd_frame)polars->pandas:pl_frame.to_pandas()

Included are a number of datasets accessible with the load_dataset() function. Let’s load the popular mtcars dataset:

from pymer4 import load_dataset

# Load the dataset

cars = load_dataset('mtcars')

# Get the columns we want

df = cars.select('mpg', 'cyl', 'wt')

# Show the first 5 rows

df.head()

| mpg | cyl | wt |

|---|---|---|

| f64 | i64 | f64 |

| 21.0 | 6 | 2.62 |

| 21.0 | 6 | 2.875 |

| 22.8 | 4 | 2.32 |

| 21.4 | 6 | 3.215 |

| 18.7 | 8 | 3.44 |

Fitting a linear model#

Let’s estimate the following univariate regression model:

We can use lm class to create a model which simply requires a formula and some data

from pymer4.models import lm

# Initialize model

model = lm('mpg ~ wt', data=df)

model

pymer4.models.lm(fitted=False, formula=mpg~wt)

Models make a copy of the input dataframe and store it in their .data attribute. As we’ll soon see, this dataframe will be augmented with additional columns after fitting a model or applying any variable transforms

model.data.head()

| mpg | cyl | wt |

|---|---|---|

| f64 | i64 | f64 |

| 21.0 | 6 | 2.62 |

| 21.0 | 6 | 2.875 |

| 22.8 | 4 | 2.32 |

| 21.4 | 6 | 3.215 |

| 18.7 | 8 | 3.44 |

We can use the .fit() method to estimate parameters and inferential statistics which are stored as inside a model object and can be accessed with a variety of methods (model.method()) or attributes (model.attribute).

model.fit()

Calling .fit() will create the following attributes for all models:

.params: parameter estimates (coefficients) for model terms.result_fit: summary style table of parameter estimates and inferential stats.result_fit_stat: model quality-of-fit statisticsaugment

.data: add fit and residual columns to the dataframe

# Inspect parameter estimates

model.params

| term | estimate |

|---|---|

| str | f64 |

| "(Intercept)" | 37.285126 |

| "wt" | -5.344472 |

We can see all this information quickly using the .summary() method (or by using .fit(summary=True)) which returns a nicely formatted great table

model.summary()

| Formula: lm(mpg~wt) | ||||||||

| Number of observations: 32 Confidence intervals: parametric --------------------- R-squared: 0.7528 R-squared-adj: 0.7446 F(1, 30) = 91.375, p = <.001 Log-likelihood: -80 AIC: 166 | BIC: 170 Residual error: 3.046 |

||||||||

| Estimate | SE | CI-low | CI-high | T-stat | df | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 37.285 | 1.878 | 33.450 | 41.120 | 19.858 | 30 | <.001 | *** |

| wt | −5.344 | 0.559 | −6.486 | −4.203 | −9.559 | 30 | <.001 | *** |

| Signif. codes: 0 *** 0.001 ** 0.01 * 0.05 . 0.1 | ||||||||

We can also print a more basic R-style summary

model.summary(pretty=False)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 37.2851 1.8776 19.858 < 2e-16 ***

wt -5.3445 0.5591 -9.559 1.29e-10 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1

Residual standard error: 3.046 on 30 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.7528, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7446

F-statistic: 91.38 on 1 and 30 DF, p-value: 1.294e-10

Or get a nice report

model.report()

We fitted a linear model (estimated using OLS) to predict mpg with wt (formula:

mpg ~ wt). The model explains a statistically significant and substantial

proportion of variance (R2 = 0.75, F(1, 30) = 91.38, p < .001, adj. R2 = 0.74).

The model's intercept, corresponding to wt = 0, is at 37.29 (95% CI [33.45,

41.12], t(30) = 19.86, p < .001). Within this model:

- The effect of wt is statistically significant and negative (beta = -5.34, 95%

CI [-6.49, -4.20], t(30) = -9.56, p < .001; Std. beta = -0.87, 95% CI [-1.05,

-0.68])

Standardized parameters were obtained by fitting the model on a standardized

version of the dataset. 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) and p-values were

computed using a Wald t-distribution approximation.

You can always directly access this information from the model attributes:

# summary table

model.result_fit

| term | estimate | std_error | conf_low | conf_high | t_stat | df | p_value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | i64 | f64 |

| "(Intercept)" | 37.285126 | 1.877627 | 33.4505 | 41.119753 | 19.857575 | 30 | 8.2418e-19 |

| "wt" | -5.344472 | 0.559101 | -6.486308 | -4.202635 | -9.559044 | 30 | 1.2940e-10 |

# Quality-of-fit statistics

model.result_fit_stats

| r_squared | adj_r_squared | sigma | statistic | p_value | df | logLik | AIC | BIC | deviance | df_residual | nobs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | i64 | i64 |

| 0.752833 | 0.744594 | 3.045882 | 91.375325 | 1.2940e-10 | 1.0 | -80.014714 | 166.029429 | 170.426637 | 278.321938 | 30 | 32 |

If we now inspect the .data attribute of the model we’ll see several new columns that have been appended to the original data. These contain model predictions, residuals, and statistics per observation

model.data.head()

| mpg | cyl | wt | fitted | resid | hat | sigma | cooksd | std_resid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f64 | i64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| 21.0 | 6 | 2.62 | 23.282611 | -2.282611 | 0.043269 | 3.067494 | 0.013274 | -0.766168 |

| 21.0 | 6 | 2.875 | 21.91977 | -0.91977 | 0.035197 | 3.093068 | 0.001724 | -0.307431 |

| 22.8 | 4 | 2.32 | 24.885952 | -2.085952 | 0.058376 | 3.072127 | 0.015439 | -0.705752 |

| 21.4 | 6 | 3.215 | 20.10265 | 1.29735 | 0.03125 | 3.088268 | 0.003021 | 0.432751 |

| 18.7 | 8 | 3.44 | 18.900144 | -0.200144 | 0.032922 | 3.097722 | 0.000076 | -0.066819 |

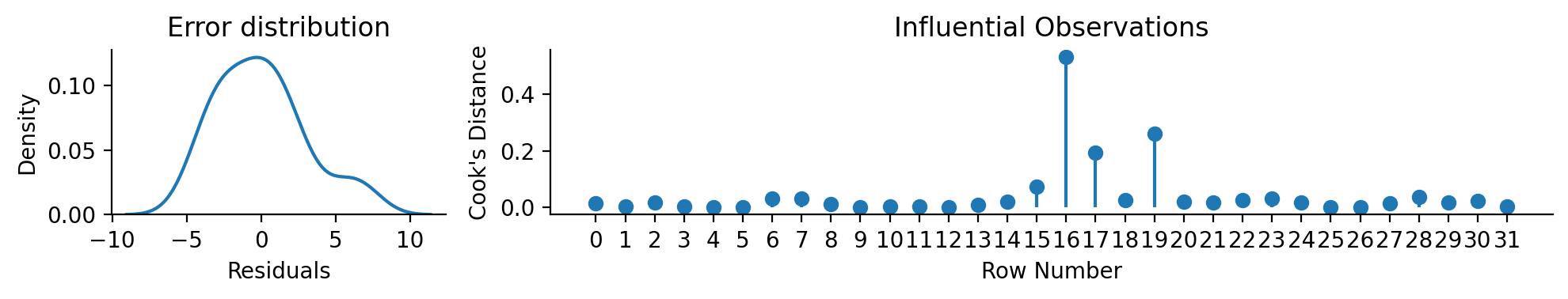

Which makes visual model inspection very easy

Show code cell source

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# Setup subplots

f = plt.figure(figsize=(10, 2))

gs = f.add_gridspec(1, 2, width_ratios=[1, 3])

left, right = f.add_subplot(gs[0]), f.add_subplot(gs[1])

# We can just use the 'resid' column for the first plot

left = sns.kdeplot(x='resid', data=model.data, ax=left)

left.set(xlabel='Residuals', title="Error distribution")

# And the 'cooksd' column to create a plot of observation influence

right.stem(model.data['cooksd'], basefmt=' ', label='Cook\'s Distance')

right.set(xlabel='Row Number', ylabel='Cook\'s Distance', title="Influential Observations", xticks=range(model.data.height))

sns.despine()

plt.tight_layout();

Categorical predictors and predictor transforms#

Let’s say we wanted to extend our model to estimate a multiple regression including an interaction with a categorical-predictor \(cyl\)

For these situations, pymer4 provides a common set of tools for manipulating the types and values of predictors:

.set/unset/show_factors(): treat variables as factors.set/show_contrasts(): specify contrast coding schemes for factors.set/unset/show_transforms(): apply a common transform to numerical predictors (e.g. centering)

We can use .set_factors() to treat \(cyl\) as a factor with levels in the specified order. Omitting a specific order will use alphabetical order by default.

We can check any currently set factor variables with .show_factors()

# Initialize model

model = lm('mpg ~ wt * cyl', data=df)

# Set cyl as a factor with levels in this order

model.set_factors({'cyl': ['4', '6', '8']})

model.show_factors()

{'cyl': ['4', '6', '8']}

Factor variables adhere to a contrast coding scheme and using treatment contrasts (dummy-coding) by default just like R. We can use .show_contrasts() to view the currently set coding scheme:

model.show_contrasts()

{'cyl': 'contr.treatment'}

For continuous predictors, we can apply common transformations using .set_transforms() (e.g. 'center', 'scale', 'zscore', 'rank').

We’ll mean-center \(wt\) so difference between levels of \(cyl\) are interpretable when \(wt\) is equal to its mean.

# Mean center wt

model.set_transforms({'wt': 'center'})

model.show_transforms()

{'wt': 'center'}

Manipulating factors and transforms changes the .data attribute of a model. We can see that cyl is now an enum type which is how polars treats categorical variables. We also have a new column wt_orig that contains the original values of \(wt\), while wt contains the transformed (mean-centered) values:

model.data.head()

| mpg | cyl | wt | wt_orig |

|---|---|---|---|

| f64 | enum | f64 | f64 |

| 21.0 | "6" | -0.59725 | 2.62 |

| 21.0 | "6" | -0.34225 | 2.875 |

| 22.8 | "4" | -0.89725 | 2.32 |

| 21.4 | "6" | -0.00225 | 3.215 |

| 18.7 | "8" | 0.22275 | 3.44 |

This makes it easy to quickly adjust predictor types and values without having to create a new model.

Caling .fit() now re-estimates the same formula on the same .data - which now has different types/values. So our parameter estimates now represent the comparisons specified by our contrasts and transformations:

mean-centered \(wt\)

treatment-coded \(cyl\) with \(4\) as the reference level

model.fit(summary=True)

| Formula: lm(mpg~wt*cyl) | ||||||||

| Number of observations: 32 Confidence intervals: parametric --------------------- R-squared: 0.8616 R-squared-adj: 0.8349 F(5, 26) = 32.362, p = <.001 Log-likelihood: -70 AIC: 155 | BIC: 165 Residual error: 2.449 |

||||||||

| Estimate | SE | CI-low | CI-high | T-stat | df | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 21.403 | 1.466 | 18.390 | 24.416 | 14.601 | 26 | <.001 | *** |

| wt | −5.647 | 1.359 | −8.442 | −2.853 | −4.154 | 26 | <.001 | *** |

| cyl6 | −1.939 | 1.756 | −5.549 | 1.671 | −1.104 | 26 | 0.2797 | |

| cyl8 | −4.589 | 1.751 | −8.188 | −0.990 | −2.621 | 26 | 0.01446 | * |

| wt:cyl6 | 2.867 | 3.117 | −3.541 | 9.275 | 0.920 | 26 | 0.3662 | |

| wt:cyl8 | 3.455 | 1.627 | 0.110 | 6.799 | 2.123 | 26 | 0.04344 | * |

| Signif. codes: 0 *** 0.001 ** 0.01 * 0.05 . 0.1 | ||||||||

ANOVA tables#

With more than 2 levels of a categorical predictor, you may be interested in an omnibus F-test across all factor levels, i.e. an ANOVA style table. To make this as easy and valid as possible (e.g. handling unbalanced designs) just create your factors with .set_factors() and use .anova() instead of .fit()

model.anova(summary=True)

| ANOVA (Type III tests) | |||||

| model term | df1 | df2 | F_ratio | p_value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt | 1 | 26 | 10.723 | 0.002993 | ** |

| cyl | 2 | 26 | 3.951 | 0.03175 | * |

| wt:cyl | 2 | 26 | 2.266 | 0.1239 | |

| Signif. codes: 0 *** 0.001 ** 0.01 * 0.05 . 0.1 | |||||

Just like .fit() the dataframe results of .anova() are accessible via .result_anova

model.result_anova

| model term | df1 | df2 | F_ratio | p_value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| "wt" | 1.0 | 26.0 | 10.723 | 0.002993 |

| "cyl" | 2.0 | 26.0 | 3.951 | 0.031753 |

| "wt:cyl" | 2.0 | 26.0 | 2.266 | 0.123857 |

Tip

You can learn more about working with transforms, factors, contrasts, and ANOVA in the categorical predictors tutorial

Marginal estimates & contrasts#

Every model supports the .emmeans() method that takes one or more predictors of the same type and generates marginal estimates while other predictors are held at their means. For example, using \(cyl\) will return the average \(mpg\) for each level of \(cyl\) while holding \(wt\) at its mean.

model.emmeans('cyl')

R messages:

NOTE: Results may be misleading due to involvement in interactions

| cyl | emmean | SE | df | lower_CL | upper_CL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cat | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| "4" | 21.403304 | 1.465893 | 26.0 | 17.66308 | 25.143528 |

| "6" | 19.464549 | 0.967159 | 26.0 | 16.996845 | 21.932253 |

| "8" | 16.814408 | 0.95775 | 26.0 | 14.370711 | 19.258106 |

Passing a continuous predictor \(wt\) to .emmeans() will calculate the average slope of that variable while other variables are held at their means. In this case the slope of \(wt\), while \(cyl\) is held at the grand-mean across factor levels.

This matches the regression parameter estimate for \(wt\) in the output of .summary() above:

model.emmeans('wt')

R messages:

NOTE: Results may be misleading due to involvement in interactions

| wt_trend | SE | df | lower_CL | upper_CL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| -3.539856 | 1.081023 | 26.0 | -5.76193 | -1.317783 |

Using the by argument allow us to subset the estimates of one predictor by another predictor.

For example, we can unpack the interaction by calculating separate slopes of \(wt\) for each level of \(cyl\)

model.emmeans('wt', by='cyl')

| cyl | wt_trend | SE | df | lower_CL | upper_CL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cat | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| "4" | -5.647025 | 1.359498 | 26.0 | -9.115782 | -2.178268 |

| "6" | -2.780106 | 2.805265 | 26.0 | -9.937736 | 4.377524 |

| "8" | -2.192438 | 0.894285 | 26.0 | -4.474204 | 0.089329 |

We can use the at argument to the reverse: explore the means for each level of \(cyl\) at a specific valued of \(wt\)

model.emmeans('cyl', at={'wt': 3})

R messages:

NOTE: Results may be misleading due to involvement in interactions

| cyl | emmean | SE | df | lower_CL | upper_CL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cat | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| "4" | 22.63012 | 1.219839 | 26.0 | 19.517702 | 25.742539 |

| "6" | 20.068527 | 0.9821 | 26.0 | 17.562699 | 22.574354 |

| "8" | 17.290715 | 1.10759 | 26.0 | 14.464702 | 20.116729 |

Using the contrasts argument, we can test specific comparisons between levels of a predictor.

# linear contrast across factor levels

# (-1 * 4) + (0 * 6) + (1 * 8)

model.emmeans('cyl', contrasts={'linear':[-1, 0, 1]})

R messages:

NOTE: Results may be misleading due to involvement in interactions

| contrast | estimate | SE | df | lower_CL | upper_CL | t_ratio | p_value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| "linear" | -4.588896 | 1.751036 | 26.0 | -8.188202 | -0.98959 | -2.620675 | 0.014464 |

Models also support the .empredict() method for even more control in generating predictions based on specific predictor values.

For example, we though we never observe a 4 cylinder vehicle that weighs more that 4000lbs, we can have the model predict the miles-per-gallon based on the estimated parameters:

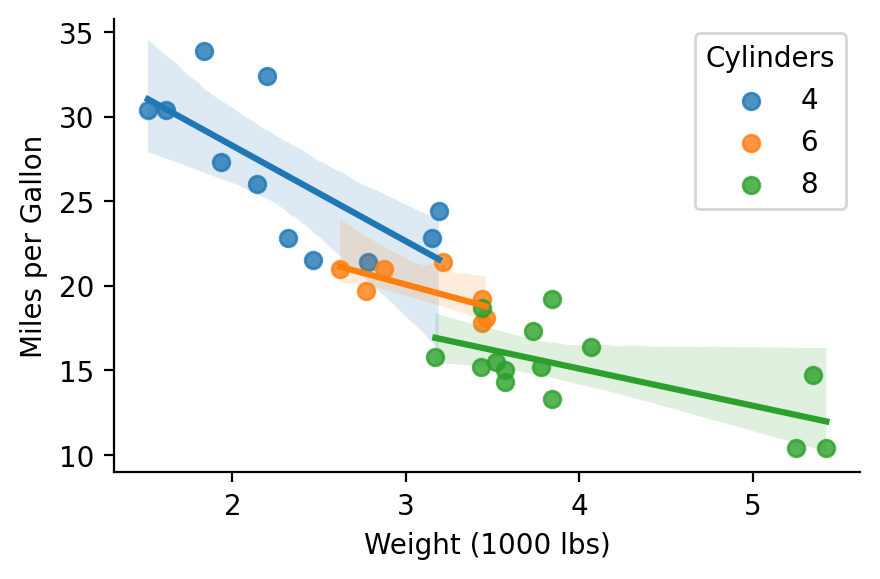

Show code cell source

import seaborn as sns

grid = sns.lmplot(x='wt_orig', y='mpg', hue='cyl', data=model.data, height=3, aspect=1.5, facet_kws={'legend_out': False})

grid.set_axis_labels("Weight (1000 lbs)", "Miles per Gallon")

grid.legend.set_title("Cylinders");

# Predict mpg when weight is 4k, 5k, and 6k

# mean-centering trasnform is appled for us

model.empredict({'wt': [4,5,6], 'cyl': '4'})

| wt | cyl | prediction | SE | df | lower_CL | upper_CL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f64 | cat | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| 0.78275 | "4" | 16.983095 | 2.444694 | 26.0 | 11.957955 | 22.008235 |

| 1.78275 | "4" | 11.33607 | 3.763179 | 26.0 | 3.600744 | 19.071395 |

| 2.78275 | "4" | 5.689044 | 5.103232 | 26.0 | -4.800798 | 16.178887 |

Multi-level models#

Working with multi-level/mixed-effects models is just as easy using lmer or glmer classes and support the same random-effects formula syntax popularized by lme4.

from pymer4 import load_dataset

from pymer4.models import lmer

sleep = load_dataset('sleep')

# Random intercept, slope, and correlation

lmm_is = lmer('Reaction ~ Days + (Days | Subject)', data=sleep)

lmm_is.fit(summary=True)

| Formula: lmer(Reaction~Days+(Days|Subject)) | |||||||||

| Number of observations: 180 Confidence intervals: parametric --------------------- Log-likelihood: -871 AIC: 1755 | BIC: 1774 Residual error: 25.592 |

|||||||||

| Random Effects: | Estimate | SE | CI-low | CI-high | T-stat | DF | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject-sd | (Intercept) | 24.741 | |||||||

| Subject-sd | Days | 5.922 | |||||||

| Subject-cor | (Intercept) | 0.066 | |||||||

| Residual-sd | Observation | 25.592 | |||||||

| Fixed Effects: | |||||||||

| (Intercept) | 251.405 | 6.825 | 237.006 | 265.804 | 36.838 | 17.000 | <.001 | *** | |

| Days | 10.467 | 1.546 | 7.206 | 13.729 | 6.771 | 17.000 | <.001 | *** | |

| Signif. codes: 0 *** 0.001 ** 0.01 * 0.05 . 0.1 | |||||||||

Multi-level models have the following additional atttributes to make working with random-effects easier:

.ranef- cluster level deviances.ranef_var- cluster level variance-covariances.fixef- BLUPs; cluster level coefficients (.params + .ranef)

# Slope and intercept for each Subject

lmm_is.fixef.head()

| level | (Intercept) | Days |

|---|---|---|

| str | f64 | f64 |

| "308" | 253.663656 | 19.666262 |

| "309" | 211.006367 | 1.847605 |

| "310" | 212.444696 | 5.018429 |

| "330" | 275.095724 | 5.652936 |

| "331" | 273.665417 | 7.397374 |

# Variance across Subject level slopes and intercepts

lmm_is.ranef_var

| group | term | estimate | conf_low | conf_high |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | str | f64 | f64 | f64 |

| "Subject" | "sd__(Intercept)" | 24.740658 | null | null |

| "Subject" | "cor__(Intercept).Days" | 0.065551 | null | null |

| "Subject" | "sd__Days" | 5.922138 | null | null |

| "Residual" | "sd__Observation" | 25.591796 | null | null |

And we can generate a summary report:

lmm_is.report()

We fitted a linear mixed model (estimated using REML and nloptwrap optimizer)

to predict Reaction with Days (formula: Reaction ~ Days). The model included

Days as random effects (formula: ~Days | Subject). The model's total

explanatory power is substantial (conditional R2 = 0.80) and the part related

to the fixed effects alone (marginal R2) is of 0.28. The model's intercept,

corresponding to Days = 0, is at 251.41 (95% CI [237.94, 264.87], t(174) =

36.84, p < .001). Within this model:

- The effect of Days is statistically significant and positive (beta = 10.47,

95% CI [7.42, 13.52], t(174) = 6.77, p < .001; Std. beta = 0.54, 95% CI [0.38,

0.69])

Standardized parameters were obtained by fitting the model on a standardized

version of the dataset. 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) and p-values were

computed using a Wald t-distribution approximation.

We can refit the model using bootstrapping to get confidence intervals around both fixed and radom effects

lmm_is.fit(conf_method='boot', summary=True)

| Formula: lmer(Reaction~Days+(Days|Subject)) | |||||||||

| Number of observations: 180 Confidence intervals: boot Bootstrap Iterations: 1000 --------------------- Log-likelihood: -871 AIC: 1755 | BIC: 1774 Residual error: 25.592 |

|||||||||

| Random Effects: | Estimate | CI-low | CI-high | SE | T-stat | DF | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject-sd | (Intercept) | 24.741 | 12.073 | 35.774 | |||||

| Subject-sd | Days | 5.922 | 3.360 | 8.370 | |||||

| Subject-cor | (Intercept) | 0.066 | −0.481 | 0.948 | |||||

| Residual-sd | Observation | 25.592 | 22.746 | 28.588 | |||||

| Fixed Effects: | |||||||||

| (Intercept) | 251.405 | 237.902 | 263.832 | 6.825 | 36.838 | 17.000 | <.001 | *** | |

| Days | 10.467 | 7.362 | 13.255 | 1.546 | 6.771 | 17.000 | <.001 | *** | |

| Signif. codes: 0 *** 0.001 ** 0.01 * 0.05 . 0.1 | |||||||||

Comparing models#

pymer4 offers a general-purpose compare() function to compare 2 or more nested models using an F-test or Likelihood-Ratio-Test. This is handy for comparing the random-effects structure of various mixed models

from pymer4.models import compare

# Random intercept only model

lmm_i = lmer('Reaction ~ Days + (1 | Subject)', data=sleep)

# Suggests modeling slopes is worth it

compare(lmm_is, lmm_i)

| Analysis of Deviance Table | |||||||||

| Model 1: lmer(Reaction~Days+(Days|Subject)) Model 2: lmer(Reaction~Days+(1|Subject)) |

|||||||||

| AIC | BIC | logLik | npar | -2*log(L) | Chisq | Df | Pr(>Chisq) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.00 | 1755.6 | 1774.8 | −871.8 | 4.00 | 1.79K | ||||

| 2.00 | 1794.5 | 1807.2 | −893.2 | 6.00 | 1.75K | 42.14 | 2.00 | <.001 | *** |

| Signif. codes: 0 *** 0.001 ** 0.01 * 0.05 . 0.1 | |||||||||

For linear models, compare() performs nested-model comparison, which is a more general purpose approach that can be used to answer the same question as the interaction F-test in the ANOVA table above

# Define model without interaction

add_only = lm('mpg ~ wt + cyl', data=df)

add_only.set_factors({'cyl': ['4', '6', '8']})

# Compare to our original model

compare(model, add_only)

| Analysis of Deviance Table | ||||||||||

| Model 1: lm(mpg~wt*cyl) Model 2: lm(mpg~wt+cyl) |

||||||||||

| AIC | BIC | logLik | Res_Df | RSS | Df | Sum of Sq | F | Pr(>F) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.00 | 155.5 | 165.7 | −70.7 | 26.00 | 155.89 | |||||

| 2.00 | 156.6 | 164 | −73.3 | 28.00 | 183.06 | −2.00 | −27.17 | 2.27 | 0.124 | |

| Signif. codes: 0 *** 0.001 ** 0.01 * 0.05 . 0.1 | ||||||||||

Summary and next steps#

This quickstart provided an overview of the core functionality when working with models in pymer4. For more in-depth tutorials check out:

linear regression tutorial which also demonstrates features common to all

pymer4modelscategorical variables tutorial if you’re working with factorial designs or non-numeric predictors

multi-level models tutorial for repeated-measures or hierarchical data

generalized linear/multi-level models tutorial for non-gaussian outcome variables (e.g. logistic regression)

scikit-learncompatible estimators using theskmerclass

You can read about the specific arguments and outputs of different model methods on their respective API pages, e.g. lm.fit()

If you’re interested in more advanced functionality, you explore the tidystats module that export many popular R functions from a variety of libraries (and powers pymer4.models !)